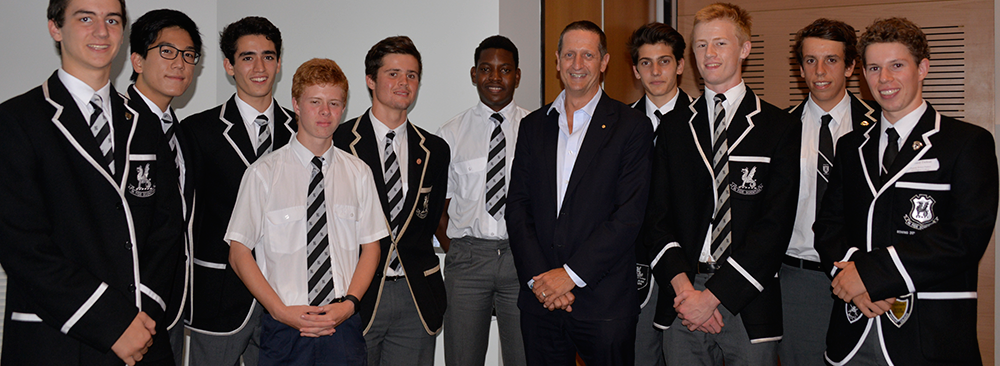

Prof Ian Hickie talks about ‘Mental Capital’

If you want to prosper socially and economically – to have a cohesive and functional society – your citizens have got to be collectively right in their heads, said Prof Ian Hickie at the first Ethics Centre public lecture for 2015.

Prof Hickie is the CEO of the Brain and Mind Research Institute at Sydney University and has been a social advocate for youth mental health issues and well-being for more than 20 years. He is also a father of a 22 year old economics major and open to new ideas. He began his lecture by talking about how his daughter introduced him to an an academic paper called the ‘Mental Wealth of Nations’ and the concept of ‘Mental Capital’ coined by the UK Government Office of Science to chart the big set of challenges that governments face as a result of mental health issues.

While fiscal realities are not often referred to when discussing well-being, the concept of ‘mental capital’ is used to describe the value of lived experiences, education, training, mentoring, co-curricular and social interaction to produce socially wired and cognitively smart citizens who are responsive and can adapt to challenges. As we live in a time that preoccupies itself with fear of ‘the other’, anxiety and uncertainty said Prof Hickie, having better ‘mental capital’ ensures a greater chance of survival.

“Staying engaged socially contributes a lot to the preservation of ‘mental capital’ across your life span, but the big issue in development is to make sure that as many of our young people and citizens get there in the first place to reach their full potential – and my main message is that it’s not over at nine months, it’s not over at one year, it’s not over at school, it isn’t over at 14 and in fact it isn’t over at 17 and 18 or when you graduate,” he said.

In fact, in Australia 40 per cent of disabilities are disabilities involving the brain or can be categorised as neurological disorders. The big peak age for boys and girls to develop a mental illness is 10 years old and many do not get treated until they reach their mid twenties when “a small anxiety turns into a big depression, and a substance abuse problem tomorrow, if left untreated.”

“There is this interesting thing over in boys – girls may not know this, but boys are actually more sensitive and more vulnerable…There are more boys with learning difficulties and neuro-mental difficulties that continue throughout their whole life and that could go on to develop into other mental problems that they take with them throughout life that could have social and other consequences.”

Unfortunately, “young people are entirely aware of the problem but they do not find that the product that we are selling very attractive,” said Prof Hickie. As a result of this there have been an emerging set of pro-social internet tools targeted towards young people to help them get treatment.

The rapidly changing, highly personalised and mobile nature of technology use among young people has been a field of research that Prof Hickie has been involved in as a way to engage effectively with young people who need help.

“Younger people today are not intrinsically part of all these things on a daily basis. So the possibility to mentoring and connection outside of the family is just not there in any kind of way, which comes back to the role of social media and technology,” he said.

The suicide prevention website Reach Out and mood tracker website MoodGYM are two examples of how pro-social technology can be accessed by youths. Prof Hickie said,”People who are stressed actually talk to people over the internet and use these media forms to seek help in a really productive way. So all those who want to regulate it and shut it down and stop it – it’ll be good if we think, ‘hang on a sec, this is one of our principle ways of actually connecting with people who are in distress on a daily basis'”.

An underlying contributor to building ‘mental capital’ is the power of institutions like schools and universities to sustain support, meaning and structure for young people as they wade through the difficulties of adolescence and young adulthood. Prof Hickie mentioned the findings of the latest Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report that outlined the issue of productivity among young people who are not in education, employment or training as an area of concern and suggests that in order to remain mentally healthly, young people need to alternate between education and experience. In addition, physical health and a sense of independence can contribute to better mental health.

“To be really mentally healthy, you require what appears to be opposite things – one is to be very autonomous – have control and feel like you have control over your own destiny – if you loose control over your own destiny your mental health tends to deteriorate very quickly.”

In relation to alcohol and substance abuse, he said that alcohol was about the best substance to knock off brain cells that researchers know of.

“If you want to go to university and do something really well then you need to say to binge drinkers – this is basically the quickest way to knock off not just brain cells but your capacity to remember things and do things like the HSC on an ongoing basis”, he said.

“So the problem for us is that if you remember me saying things about brain development and the frontal lobe developing around the age of 15 and 16 years old, then you’ll understand the dangers of starting to drink at that age as well”.

Many thanks to Prof Hickie for kick-starting the first Centre for Ethics talks for 2015. If you would like to find out more about the upcoming talks check out the Centre for Ethics Insite here.