A Message from the Head of Lindfield Campus

Most Likely To Succeed

Contemporary education is grappling with some very large questions about the evolution of education and our role of preparing our boys for a very new and ill-defined future. On 3 March, Newington Lindfield is hosting a screening of a documentary called ‘Most Likely To Succeed’. This movie raises critical questions about the nature of contemporary education and how best we help our boys prepare for an exciting future. It is important to get as many parents as possible to come along and be part of the discussion.

I would like to start this conversation in Prep Talk with an extract from an interesting article from Ed. Magazine summarized below by Kim Marshall. This article reports on the recent thinking of David Perkins (Harvard Graduate School of Education) one of the influential thinkers on education of our times (the education equivalent of a rock star)! This article starts the discussions that will continue with our movie screening on what’s worth learning in school.

“What’s Worth Learning in School?”

Perkins says there’s often a skeptical student at the back of the class who asks, “Why do we need to know this?” Lots of teachers, including Perkins, find this an uncomfortable moment: “When that ballistic missile comes from the back of the room, it’s a good reminder that the question doesn’t just belong to state school boards, authors of textbooks, writers of curriculum standards, and other elites. It’s on the minds of our students.”

The fact is that we teach a lot that isn’t going to matter in students’ lives, says Perkins – and we don’t teach a lot of stuff that really will matter. Why? Because of three rival learning agendas:

- Information – Students are asked to master a vast body of stuff, even though much of it won’t matter, in any meaningful way, to their lives. “It’s nice to know things,” says Perkins. “I like to know things. You like to know things. But there are issues of balance, particularly in the digital age… the world we are educating learners for is something of a moving target.” The problem is that the conventional curriculum is “chained to the bicycle rack,” he says – parents demand it, textbooks convey it, teachers are required to teach it, and we don’t feel comfortable throwing it out. But knowledge without utility has a short half-life. “The hard fact is that our minds hold on only to knowledge we have occasion to use in some corner of our lives,” he says. “Overwhelmingly, knowledge unused is forgotten. It’s gone.”

- Achievement – The pressure to do well on high-stakes summative tests is a life-support system for the conventional curriculum, but this type of testing “makes for shallow learning and understanding,” says Perkins. “You cram and do well on the test but may not have the understanding. It unravels.” Besides, is it important to know state capitals and major rivers? Perkins argues that what matters is how the location of rivers and harbors and other features of the land have been shaped by and continue to shape the course of history. Better than learning facts about the French Revolution, understand how those events relate to world conflict, poverty, and the struggle between church and state. “All that talk about achievement leaves little room for discussion about what’s being achieved,” says Perkins. Besides, less-formal, more frequent formative assessment produces much better learning.

- Expertise – The Holy Grail of education is becoming an expert – for example, in math, moving through algebra, geometry, and reaching the pinnacle, calculus, “an entire subject that hardly anybody ever uses,” says Perkins. But any time there’s push-back on the conventional curriculum, supporters claim, “We’re sacrificing rigor!” Perkins would rather that schools prepare students to be “expert amateurs” in, for example, statistics, appreciating art, understanding insurance rates, filing taxes, raising children – areas with immediate relevance to daily life.

In short, Perkins believes we need to rethink curriculum content in a radical way. Historically, we’ve focused K-12 schooling on educating for the known, “the tried and true, the established canon,” he says. “This made very good sense in the many periods and places where most children’s lives were likely to be more or less like their parents’ lives. However, wagering that tomorrow will be pretty much like yesterday does not seem to be a very good bet today. Perhaps we need a different vision of education, a vision that foregrounds educating for the unknown as much as for the known.”

Perkins likes to tell the story of Mahatma Gandhi losing one of his sandals as he boarded a moving train in India. There wasn’t time to retrieve the sandal on the ground, and without hesitation, Gandhi took off his other sandal and threw it toward the first. Asked by a colleague what he was thinking, Gandhi said one sandal wouldn’t do him any good, but two would certainly help someone else. Gandhi “showed wisdom about what to keep and what to let go of,” says Perkins. “Those are both central questions for education as we choose for today’s learners the sandals they need for tomorrow’s journey.”

Here at Lindfield, we are already looking at the way we educate our boys. We are a PYP school and so we naturally want our boys to be asking the probing questions that help us think in new and unique ways.

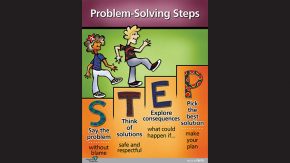

Education is evolving quickly and as an independent school we are in the lucky position to be relatively agile is the way we work with our boys. We realise that the essential foundations around numeracy and literacy are our building blocks for higher order thinking but we are acutely conscious that our boys need to be flexible, resilient individuals who are adept problem solvers and collaborative learners in order to meet the complex educational paradigms of our time.

“What’s Worth Learning in School?” by Lory Hough in Ed. Magazine, Winter 2015 (p. 36-41), www.gse.harvard.edu/ed