Mindfulness

Social and Emotional Learning can help students develop the understanding, strategies and skills that support a positive sense of self, promote respectful relationships and build student capacity to recognise and manage their own emotions and make responsible decisions.

In support of our PALS program incorporating the Second Step program we are investigating current research on the importance of well-being, social skill development and resilience, and our observations of the needs of our boys to address their social emotional learning needs. One area of research that we are investigating is centered around Mindfulness and how we can implement a structured mindfulness program to support our boys and staff.

Mindfulness simply means paying attention to the present moment with kindness and curiosity and without judgment. It’s intentionally drawing your awareness to thoughts, feelings, or sensations happening from moment to moment.

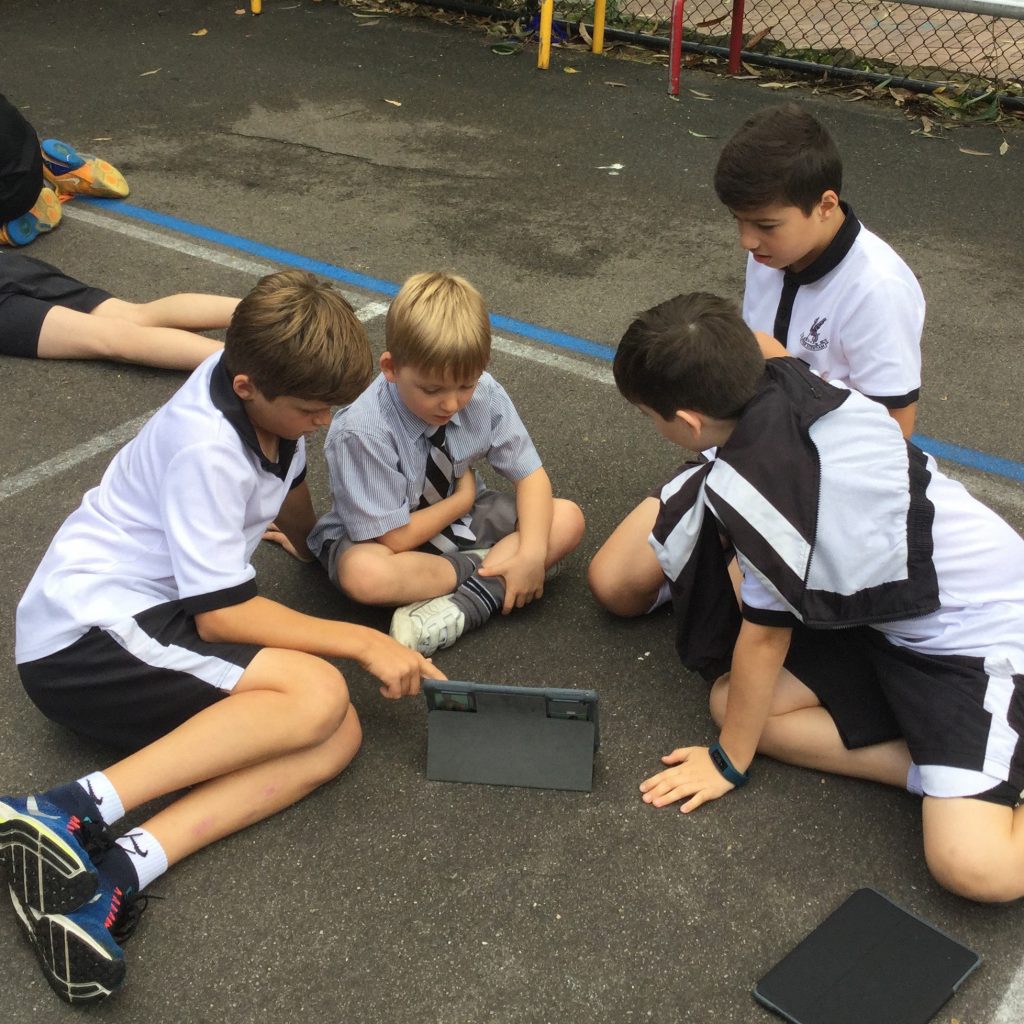

Mind Yeti is a new resource from Committee for Children that will help kids reduce stress, improve focus, and build empathy through mindfulness. Research shows that mindfulness strengthens the regions of the brain that help us regulate emotions and solve problems. Mind Yeti will make it easy for kids and adults to tap into the power of mindfulness together.

Mind Yeti sessions are designed to help children practice mindfulness by learning how to focus their attention, regulate their emotions, and explore empathy and compassion. These mindfulness skills are a subset of the social-emotional skills taught in the Second Step program. Mind Yeti strengthens and complements the Second Step program.

As a school, we are currently trialing the use of Mind Yeti to address mindfulness and will re-evaluate its use at the end of this term. Any feedback that you may have around mindfulness is welcome.

Pascal Czerwenka – Deputy Head of Campus

For your interest and further reading:

Mindfulness Research (taken from http://blog.mindyeti.com/mindfulness-research)

Key Finding #1: Mindfulness can work, for adults and kids.

Mindfulness has been defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003, p. 145). Studies have found that the trait, mindfulness, is associated with indicators of well-being, including optimism, positive feelings, and self-actualisation and has been linked to lower rates of psychological and emotional disturbance in both adults and younger populations (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Lawlor, Schonert-Reichl, Gadermann, & Zumbo, 2014). In addition, studies with adults have found a relationship between mindfulness and emotional intelligence (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003). With regards to the cultivation of mindfulness, mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have shown promise in promoting social emotional skills and indicators of well-being in children and youth (for reviews, see Burke, 2010; Greenberg & Harris, 2012; Harnett & Dawe, 2012). In addition, researchers who conducted a meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of MBIs with youth concluded that MBIs are a promising approach that warrants further application and investigation. (Zoogman, Goldberg, Hoyt, & Miller, 2014).

Key Finding #2: Mindfulness can help people calm down, focus, and connect.

Empirically, mindfulness has been found to support emotion regulation, attention, and positive relationships. Mindfulness involves an active process to attend to the present moment. This requires focus, the ability to control attention, and exercise executive functions (Zelazo & Lyons, 2012). Executive functions are high-level functions that are central to planning behavior to achieve goals, including inhibiting impulses and responses that may derail goal-directed behavior (Diamond, 2013; Diamond & Lee, 2011). Research has shown that mindfulness training can improve cognitive control, an important aspect of attention and self-regulation in children and adults (Flook et al., 2010; Jha, Krompinger, & Baime, 2007; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2007; Tang & Posner, 2009).

Key Finding #3: Mindfulness is associated with improved emotional awareness.

Awareness of emotions is a critical component of emotion regulation. Mindfulness is associated with the ability to better describe and identify emotions (Dekeyser, 2008). The open and accepting nature of a mindful state lends itself to effective emotion regulation. Present-moment awareness enables people to be tuned in to changes in their emotions. This present-moment awareness and acceptance work iteratively, in that “awareness facilitates acceptance by effectively detecting the affective cues that are then ‘accepted,’ which facilitates awareness by fostering an open mindset that allows for cue detection. Thus, mindfulness promotes executive control by enhancing experience of and attention to transient affects—the control alarms—that arise from competing goal tendencies” (Teper, Segal, & Inzlicht, 2014, p. 4).

Key Finding #4: Mindfulness supports social connection.

Mindfulness also has been found to support social connection. In particular, research has found trait mindfulness to be related to, or predictive of, openness, interpersonal closeness, and relatedness (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Recent investigations of MBIs with adults have shown improvements in social-emotional functioning, including empathy (Sahdra et al., 2011) and prosocial responding (Kemeny et al., 2012), suggesting a connection between mindfulness practice, empathy, and prosocial behaviour. Similarly, research with children has found improvements in prosocial behaviours as rated by peers, and self- reported improvements in empathy (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2014).

References

For your reference, here’s a list of some of the key research publications that informed the thinking behind Mind Yeti.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 133–144.

Brown. K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Dekeyser, et al. (2008). Mindfulness skills and interpersonal behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(5), 1235-1245.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168.

Diamond, A., & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4–12 years old. Science, 333(6045), 959–964. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204529

Flook. L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenalnd, S., Locke, J, … Kasari, C. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26, 70–95.

Greenberg, M. T., & Harris, A. R. (2012). Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: Current state of research. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 161–166.

Harnett, P. H., & Dawe, S. (2012). Review: The contribution of mindfulness-based therapies for children and families and proposed conceptual integration. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(4). doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00643.x

Jha, A. P., Krompinger, J., & Baime, M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(109). doi:10.3758/CABN.7.2.109

Kemeny, M. E., Foltz, C., Cavanagh, J. F., Cullen, M., Giese-Davis, J., Jennings, P., … Ekman, P. (2012). Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional behavior and promotes prosocial responses. Emotion, 12(2), 338–350. doi: 10.1037/a0026118

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Lawlor, M. S., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Gadermann, A. M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2014). A validation study of the mindful attention awareness scale adapted for children. Mindfulness, 5, 730. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0228-4

Sahdra, B. K., MacLean, K. A., Ferrer, E., Shaver, P. R., Rosenberg, E. L., Jacobs, T. L., … Saron, C. D. (2011). Enhanced response inhibition during intensive meditation training predicts improvements in self-reported adaptive socioemotional functioning. Emotion, 11, 299–312.

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Oberle, E., Lawlor, M. S., Abbott, D., Thomson, K., Oberlander, T. F., & Diamond, A. (2015). Enhancing cognitive and social-emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 52–66. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0038454

Tang, Y.-Y., Ma, Y., Wang, J., Fan, Y., Feng, S., Lu, Q., … Posner, M. I. (2007). Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(43), 17152–17156. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707678104

Tang, Y. Y., & Posner, M. I. (2009). Attention training and attention state training. Trends in Cognitive Science, 13(5), 222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.009

Teper, R., Segal, Z. V., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Inside the mindful mind: How mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 449–554.

Zelazo, P. D., & Lyons, K. E. (2012), The potential benefits of mindfulness training in early childhood: A developmental social cognitive neuroscience perspective. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 154–160. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00241.x

Zoogman, S., Goldberg, S. B., Hoyt, W. T., Miller, L. (2015). Mindfulness interventions with youth: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6, 290. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0260-4