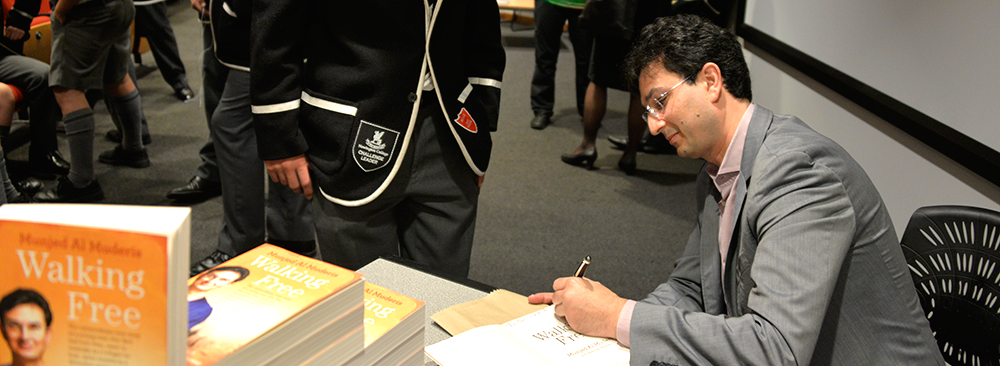

Dr Al Muderis’ story of Walking Free

While Baghdad today is a city scarred by war and terror, the guest speaker at the second Centre for Ethics Lecture for 2015, Dr Munjed Al Muderis remembers it as a beautiful and cosmopolitan city in 1999 when he was a junior surgeon at Baghdad’s Saddam Hussein Medical Centre.

However at about 8:30 AM one morning in October 1999, everything changed. Saddam Hussien’s Republican Guards entered the hospital where he was working the morning shift and ordered surgeons and nurses to amputate the ears of deserters. In a desperate attempt to avoid harming patients Al Mudaris hid in a toilet cubicle and knew at that moment that he had to flee Baghdad or be shot for refusing to carry out the barbaric punishment. From here on began his terrifying journey as a political refugee and asylum seeker.

After hiding in the toilet cubicle for more than five hours, Al Muderis managed to escape from the hospital and soon later arrived in Jordan. Quickly he realised there was no security in Jordan either as the Jordanian King backed Hussein’s Iraqi Republican Guard.

“As an Iraqi national, no country would give me a visa except Malaysia. There are no ‘middle ground’ countries in which you can seek refugee status,” he explained.

“There is no queue jumping when you are a refugee – there simply is no queue. It is a matter of making yourself useful as an asylum seeker, having money or having connections. Everyone has connections.”

The story of his escape to Malaysia; the precarious boat trip with 165 others to Christmas Island; and the move to Curtin Detention Center in Western Australia had him experience humanity at its best and worst, in unlikely places and from unlikely helpers.

“I met ‘respectable’ smugglers. I did what I was told and I had to trust that they would honour what they promised. They did. I followed their instructions including putting money in my passport at borders to buy co-operation and entry from customs officials”, he said.

Kindness was found in the unexpected gesture from the Australian Federal Police Officer on Christmas Island who, against all regulations, insisted Al Muderis use his own personal phone to ring his mother, “to just let her know you are safe and alive”, he recounted.

Inhumane treatment was experienced at the Australasian Correctional Management (ACM) at Curtin Detention where one employee punished Al Muderis by shutting him in confinement, supposedly on ‘suicide watch’, after he was accused of leading breakout protests.

“The handling of refugees in Australia is poor”, said Al Muderid.

“We need to remember we are all human. We need to bring what it is to be human to the table first,” he advised.

“And we need people who can work in this country – let them contribute rather than drain the resources of the government that keeps them in detention.”

Fifteen years since his release from Curtain Detentions Centre, Dr Al Muderis is a pioneer in medical osseointegration—prosthetics for amputees. He has played an enormous role in putting Australia at the forefront of this ground-breaking robotic science; not in the least by ensuring the titanium devices he has designed have Australian patents and manufacturing rights.

Dr Munjed Al Muderis is extraordinary proof that the asylum seeker who flees in terror, who may have queue jumped, depending on how you view his entry to Australia, can make an enormous contribution to this county if allowed the freedom and dignity to work hard. He knows asylum seekers in detention cling to this hope, just to survive.

The lecture identified, in one man’s story, many ethical reasons to continue to question the social justice in any legislation, policy or process that detains persons in prison conditions and inactivity for years, on the basis of their arrival in this country by unsafe and desperate means.

We must not forget that the desperation inherent in refugees’ and asylum seekers’ stories is because the avenues to safety and justice in their homelands are clearly and irrevocably closed.